Update

Breaks Ground

A 40-Year Project Breaks Ground

ast summer, Jonathan Tymick got stuck behind a travel trailer with a flat tire on the Seward Highway near Cooper Landing. The Alaska Department of Transportation and Public Facilities, or DOT&PF, project manager watched as the trailer continued along the two-lane highway until the driver found a safe place to pull off.

“That gentleman drove about a mile and completely damaged his rim,” Tymick says. “That was kind of eye opening.”

The trailer driver’s misfortune is emblematic of the need for the Sterling Highway Milepost 45 to 60 Project, colloquially known as the Cooper Landing Bypass. Built in the ‘40s, the highway as it exists today does not meet current design standards: the corners are too sharp and, as the travel-trailer driver found, there are few to no shoulders to pull onto in case of emergency.

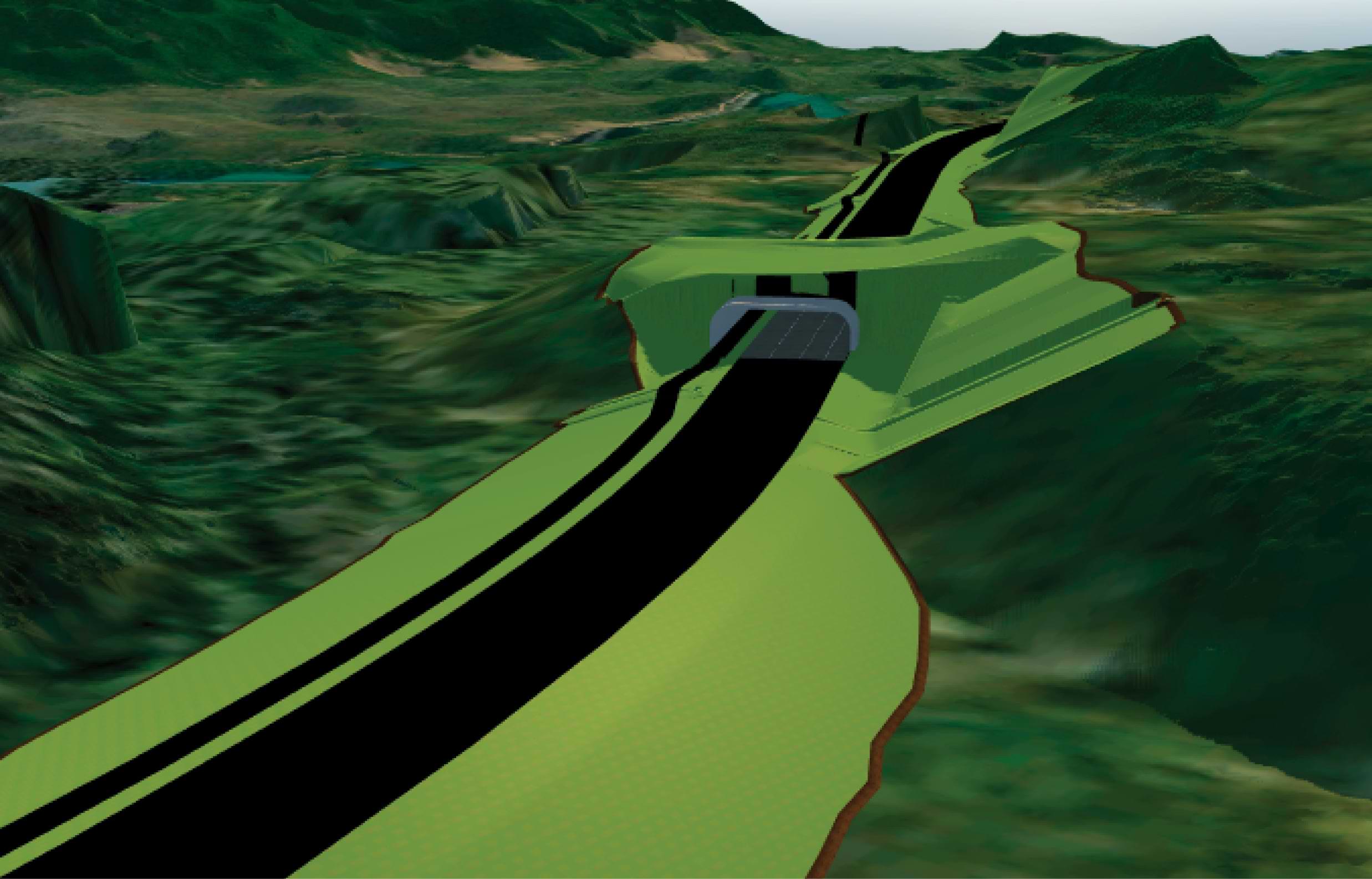

A project forty years in development, the Cooper Landing Bypass will build ten miles of new road north of Cooper Landing; reconstruct existing road to widen shoulders and add passing lanes, paths, and wildlife crossings; and generally increase safety for drivers, pedestrians, and local animals.

While road construction is never fun for drivers making their way along the Sterling Highway, the end result will offer a faster route around Cooper Landing. Vehicles must currently slow to 35 miles per hour to pass through Cooper Landing, and the new bypass will post speed limits of 55 miles per hour.

Traffic analysis predicts that once the project is open, roughly 70 percent of traffic will use the bypass, making Cooper Landing less congested.

To access the bypass, project contractor QAP/Traylor Joint Venture, or JV, has upgraded two existing roads to provide access to the alignment and ultimately to Juneau Creek Canyon, where a new steelplate girder bridge will be placed.

The project also includes five dedicated wildlife crossings, including the fi rst wildlife overpass in the state of Alaska.

Traffic impacts will be minor this summer, Tymick says, as construction of Milepost 56 to 58 is completed. This phase includes soil stabilization to prevent slopes from encroaching into designated wilderness areas north of the corridor and the construction of wildlife undercrossings, retaining walls, and erosion protection measures.

However, traffic will be detoured for several years starting in 2024 between Milepost 45 and 47 as construction begins on that two-mile section of road and materials are brought in to build the Juneau Creek Bridge.

At 928 feet, the bridge will be the longest fully erected and launched bridge in the nation. It was developed through the Construction Manager/General Contractor, or CMGC, process with QAP/ Traylor JV, which allowed DOT&PF to optimize the design.

“The department has been utilizing the CMGC process for years, though not to this scale,” says Elmer Marx, DOT&PF lead designer on the bridge. “I suspect that other states will be more interested in this collaborative eff ort with our contractor to find the best answer for both the design team and the construction team.”

The final design calls for a bridge that will be built east of its final location then rolled to Juneau Creek Canyon and launched across—a process that will happen over the span of a couple days. To cantilever the bridge, the construction crew will build a hundred-foot-tall tower with cable stays tied to the ends of the bridge girders that will extend over the canyon.

“It will take roughly one construction season to fabricate, transport, and erect the steel. But the actual launch won’t be a very long process,” explains Marx.

When finished, the Juneau Creek Bridge will be “fairly conventional looking,” he adds. But the exposed steel and the concrete steel pipe casings that support the piers will be sprayed with molten zinc.

This finish will encase the steel, essentially cutting it off from the atmosphere and, more importantly, providing a passive cathodic protection system.

“The zinc coating will provide very significant improvements to the durability and longevity of the bridge,” Marx says.

The concrete filled steel pipes that support the bridge, meanwhile, are “excellent for high seismic zones, so in the event of an earthquake there should be minimal damage or repairable damage, so that any bridge closure after a large seismic event would be minimized.”

The Cooper Landing Bypass project was initiated in the ‘70s, when a lengthy planning and environmental process began. It’s a notably complex project, thanks to its location within the Sqilantnu Archaeological District, wildlife impacts, and concerns over reducing the spread of invasive weeds during excavation, and the necessary acquisition of rights-of-way.

Working with the Kenaitze Indian Tribe and cultural resource professionals, DOT&PF developed training resources to guide personnel in recognizing archeological material. In accordance with the project’s programmatic agreement, DOT&PF archaeologists and cultural resource professionals, including local tribal participants, will maintain a presence onsite to mitigate adverse effects to cultural resources through monitoring and data recovery. All contractors and subcontractors are also trained in identifying and reporting both cultural resources and invasive species.

DOT&PF is acquiring several types of rights-of-way for the project, including private, Kenai Peninsula Borough, and federal easements, and most notably a land swap between Cook Inlet Region, Inc., or CIRI, and the US Fish & Wildlife Service, a move required by Congress under the conditions of the Russian River Lands Act. DOT&PF is currently working with CIRI to acquire the land necessary for the project and complete the land swap.

Excavation performed by QAP/Traylor JV will move more than 5 million cubic yards of material. Working with DOT&PF and engineers from DOWL (for Phase 3) and from R&M Consultants (for Phase 1B), QAP/Traylor JV will use roughly 1.1 million yards of excess material from Phase 1B to get Phase 3 to its final grade. QAP/Traylor JV also aims to balance Phases 4 and 5, eliminating the need to move material off the site or bring in any new material.

Some of that material will be used to build up site grades, while some will be used to produce the hot rock needed to make asphalt needed for the project’s roads.

“Any waste on the material will stay within the project,” explains Mike Fizette, the project’s manager and single point of contact for DOT&PF at QAP/Traylor JV.

Working together to eliminate project waste is another advantage of the CMGC process used on this project. With a $690 million budget, the cost savings made possible through collaboration and discussion has been a major advantage, Fizette says.

For example, QAP/Traylor JV was able to delay building the wildlife overpass, originally part of Phase 4, when planners noted that equipment needed after Phase 4 wouldn’t fit under it.

“This process has allowed us to express why we want to do things a certain way and how it will be better for time and the cost of the project,” Fizette says. “The cost of the CMGC process itself is easily paid for by what we save through collaborating and planning together.”

The project is expected to wrap up and be open to the traveling public in late 2027.